Code

x <- c(2, 5, 1, 8, 3)

x[1] 2 5 1 8 3Matrix algebra (linear algebra) is the mathematical foundation for many statistical and machine learning methods. Understanding matrices is essential for:

This appendix introduces the key concepts and R operations you need to work with matrices effectively.

A scalar is a single number. In matrix notation, scalars are typically denoted with lowercase letters:

\[a = 5, \quad b = 3.14\]

A vector is an ordered collection of numbers. In R, we create vectors with c():

x <- c(2, 5, 1, 8, 3)

x[1] 2 5 1 8 3Mathematically, we write a column vector as:

\[ \mathbf{x} = \begin{pmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ \vdots \\ x_n \end{pmatrix} \]

Vectors are typically denoted with bold lowercase letters. The transpose operation \(^\top\) converts a column vector to a row vector:

\[\mathbf{x}^\top = (x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n)\]

A matrix is a rectangular array of numbers arranged in rows and columns. We can create matrices in R by binding vectors:

x_1 <- 1:5

x_2 <- 6:10

X <- cbind(x_1, x_2)

X x_1 x_2

[1,] 1 6

[2,] 2 7

[3,] 3 8

[4,] 4 9

[5,] 5 10Mathematically, an \(n \times p\) matrix (n rows, p columns) is written as:

\[ \mathbf{X} = \begin{pmatrix} x_{1,1} & x_{1,2} & \cdots & x_{1,p} \\ x_{2,1} & x_{2,2} & \cdots & x_{2,p} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ x_{n,1} & x_{n,2} & \cdots & x_{n,p} \end{pmatrix} \]

Matrices are denoted with bold uppercase letters. The element in row \(i\) and column \(j\) is written as \(x_{i,j}\).

The dimension of a matrix is its number of rows × number of columns:

# Load MNIST data for examples

if (!exists("mnist")) mnist <- read_mnist()

x <- mnist$train$images[1:1000, ]

y <- mnist$train$labels[1:1000]

dim(x)[1] 1000 784This matrix has 1,000 rows (observations) and 784 columns (features—one per pixel).

nrow(x) # Number of rows[1] 1000ncol(x) # Number of columns[1] 784R vectors don’t have dimensions:

v <- 1:5

dim(v)NULLTo treat a vector as a matrix, use as.matrix():

dim(as.matrix(v))[1] 5 1matrix() FunctionCreate a matrix from a vector by specifying dimensions:

my_vector <- 1:12

mat <- matrix(my_vector, nrow = 3, ncol = 4)

mat [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

[1,] 1 4 7 10

[2,] 2 5 8 11

[3,] 3 6 9 12By default, matrices are filled by column. Use byrow = TRUE to fill by row:

mat_byrow <- matrix(my_vector, nrow = 3, ncol = 4, byrow = TRUE)

mat_byrow [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

[1,] 1 2 3 4

[2,] 5 6 7 8

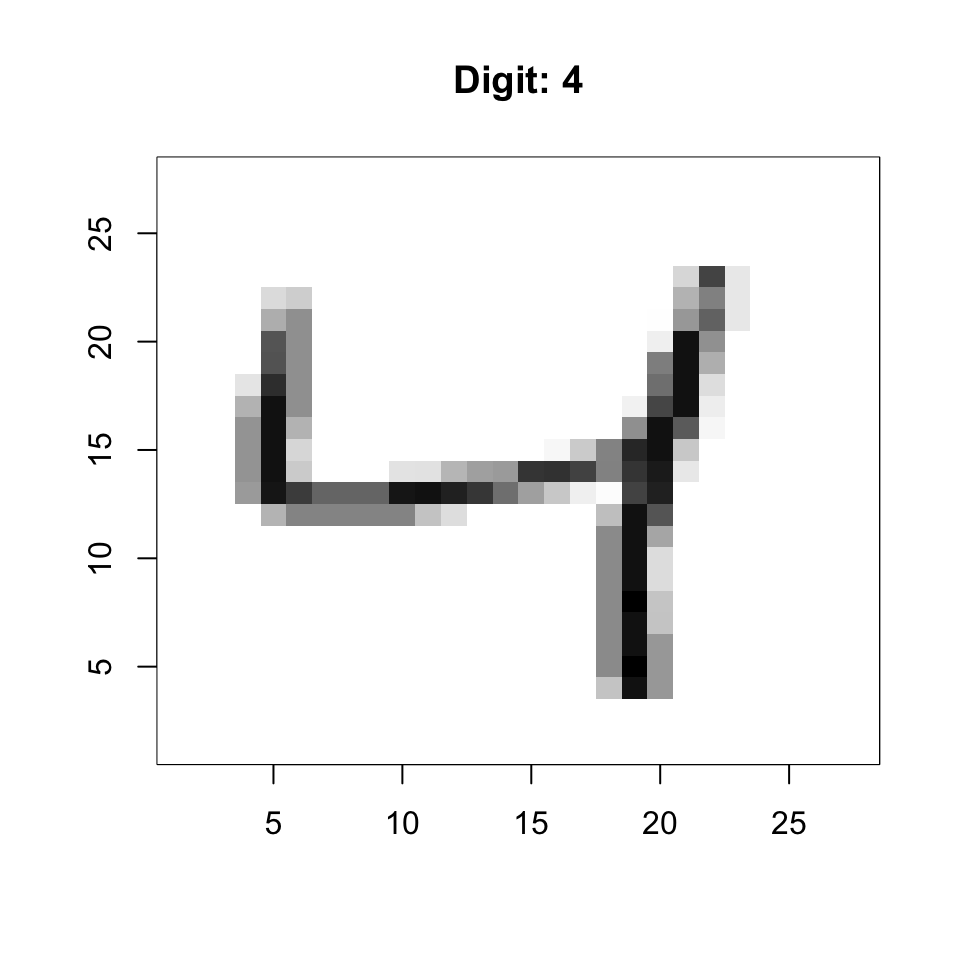

[3,] 9 10 11 12A powerful application is reshaping a vector into a 2D image. Each row of the MNIST data is a 784-element vector representing a 28×28 pixel image:

# Convert the 3rd digit to a grid

grid <- matrix(x[3, ], 28, 28)

# Display (flip to show correctly)

image(1:28, 1:28, grid[, 28:1], col = gray.colors(256, start = 1, end = 0),

xlab = "", ylab = "", main = paste("Digit:", y[3]))

The transpose swaps rows and columns:

mat <- matrix(1:6, nrow = 2, ncol = 3)

mat [,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 1 3 5

[2,] 2 4 6t(mat) [,1] [,2]

[1,] 1 2

[2,] 3 4

[3,] 5 6Use [row, column] notation:

mat <- matrix(1:12, nrow = 3, ncol = 4)

# Single element

mat[2, 3][1] 8# Entire row

mat[2, ][1] 2 5 8 11# Entire column

mat[, 3][1] 7 8 9# Multiple rows/columns

mat[1:2, 3:4] [,1] [,2]

[1,] 7 10

[2,] 8 11Extracting a single row or column returns a vector by default:

class(mat[, 1])[1] "integer"Use drop = FALSE to keep it as a matrix:

class(mat[, 1, drop = FALSE])[1] "matrix" "array" Select elements based on conditions:

mat <- matrix(1:12, nrow = 3, ncol = 4)

mat[mat > 6] <- 0 # Set values > 6 to zero

mat [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

[1,] 1 4 0 0

[2,] 2 5 0 0

[3,] 3 6 0 0This is useful for operations like binarizing data:

# Binarize MNIST data (convert to 0/1)

bin_x <- (x > 127) * 1Compute summaries across rows or columns:

# Row sums and means

row_sums <- rowSums(x)

row_means <- rowMeans(x)

# Column sums and means

col_sums <- colSums(x)

col_means <- colMeans(x)For standard deviations, use the matrixStats package:

library(matrixStats)

row_sds <- rowSds(x)

col_sds <- colSds(x)apply() FunctionApply any function across rows (margin = 1) or columns (margin = 2):

# Row medians

row_medians <- apply(x, 1, median)

# Column ranges

col_ranges <- apply(x, 2, function(col) max(col) - min(col))Remove low-variance columns (uninformative pixels):

# Keep only columns with SD > 60

sds <- colSds(x)

x_filtered <- x[, sds > 60]

dim(x_filtered)[1] 1000 314This removes over half the predictors while keeping informative features.

Standard arithmetic operates element-by-element:

A <- matrix(1:4, 2, 2)

B <- matrix(5:8, 2, 2)

A + B # Addition [,1] [,2]

[1,] 6 10

[2,] 8 12A * B # Element-wise multiplication [,1] [,2]

[1,] 5 21

[2,] 12 32A / B # Element-wise division [,1] [,2]

[1,] 0.2000000 0.4285714

[2,] 0.3333333 0.5000000When operating with vectors, R recycles along columns:

mat <- matrix(1:6, nrow = 2, ncol = 3)

vec <- c(10, 20)

mat + vec # Adds 10 to row 1, 20 to row 2 [,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 11 13 15

[2,] 22 24 26sweep() FunctionFor more control over row/column operations:

# Subtract column means (center the data)

x_centered <- sweep(x, 2, colMeans(x))

# Divide by column SDs (standardize)

x_standardized <- sweep(x_centered, 2, colSds(x), FUN = "/")For row operations, use margin = 1:

# Subtract row means

x_row_centered <- sweep(x, 1, rowMeans(x))Matrix multiplication is not element-wise. For matrices \(\mathbf{A}\) (\(n \times k\)) and \(\mathbf{B}\) (\(k \times p\)), the product \(\mathbf{C} = \mathbf{AB}\) is an \(n \times p\) matrix where:

\[c_{i,j} = \sum_{l=1}^{k} a_{i,l} \cdot b_{l,j}\]

The number of columns in \(\mathbf{A}\) must equal the number of rows in \(\mathbf{B}\).

In R, use %*% for matrix multiplication:

A <- matrix(1:6, nrow = 2, ncol = 3)

B <- matrix(1:6, nrow = 3, ncol = 2)

A %*% B [,1] [,2]

[1,] 22 49

[2,] 28 64The cross product \(\mathbf{X}^\top\mathbf{X}\) is fundamental in statistics:

# Using matrix multiplication

XtX <- t(x) %*% x

# More efficient built-in function

XtX <- crossprod(x)The cross product creates a \(p \times p\) matrix where element \((i,j)\) is the dot product of columns \(i\) and \(j\).

Multiplying a matrix by a vector transforms the vector:

A <- matrix(c(2, 0, 0, 3), nrow = 2) # Scaling matrix

v <- c(1, 1)

A %*% v [,1]

[1,] 2

[2,] 3This concept is central to understanding eigenanalysis and PCA.

For centered data \(\mathbf{X}\) (column means = 0), the covariance matrix is:

\[\mathbf{\Sigma} = \frac{1}{n-1} \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X}\]

# Center the data

x_centered <- scale(x, center = TRUE, scale = FALSE)

# Compute covariance matrix

cov_matrix <- cov(x_centered)

dim(cov_matrix)[1] 784 784The covariance matrix is: - Symmetric: \(\Sigma_{ij} = \Sigma_{ji}\) - Positive semi-definite: All eigenvalues ≥ 0 - Diagonal elements: Variances of each variable - Off-diagonal elements: Covariances between variables

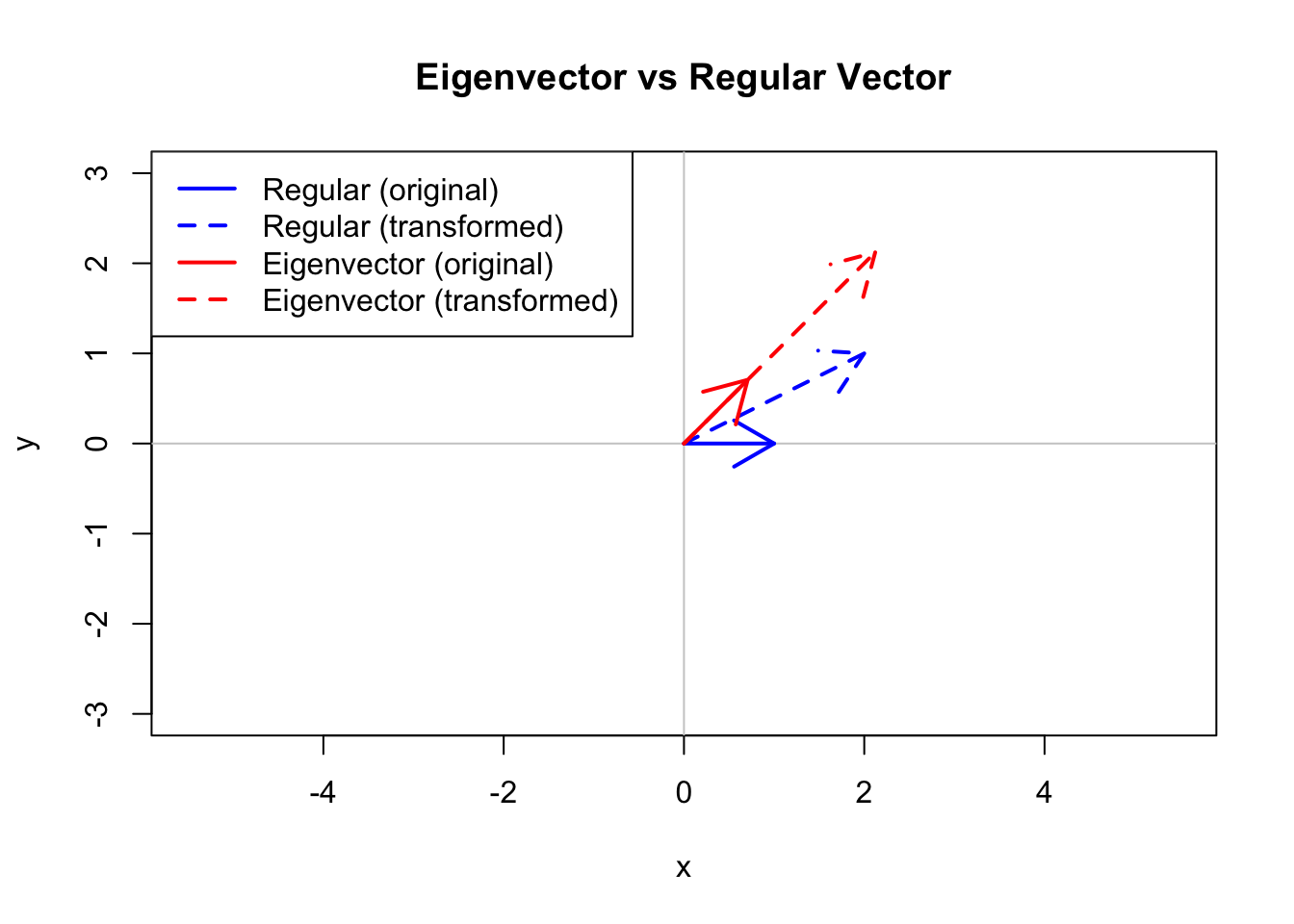

Eigenanalysis is the mathematical foundation of Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Understanding eigenvalues and eigenvectors helps you interpret PCA results correctly.

For a square matrix \(\mathbf{A}\), an eigenvector \(\mathbf{v}\) and its corresponding eigenvalue \(\lambda\) satisfy:

\[\mathbf{A}\mathbf{v} = \lambda\mathbf{v}\]

This equation says that when we multiply \(\mathbf{A}\) by \(\mathbf{v}\), the result is just \(\mathbf{v}\) scaled by \(\lambda\). The eigenvector’s direction doesn’t change—only its magnitude.

Most vectors change direction when multiplied by a matrix. Eigenvectors are special—they only get stretched or compressed:

# Define a transformation matrix

A <- matrix(c(2, 1, 1, 2), nrow = 2)

# Compute eigenvectors

eig <- eigen(A)

# Regular vector (changes direction)

v_regular <- c(1, 0)

v_transformed <- A %*% v_regular

# Eigenvector (only scales)

v_eigen <- eig$vectors[, 1]

v_eigen_transformed <- A %*% v_eigen

# Plot

plot(NULL, xlim = c(-3, 3), ylim = c(-3, 3), asp = 1,

xlab = "x", ylab = "y", main = "Eigenvector vs Regular Vector")

abline(h = 0, v = 0, col = "gray80")

# Regular vector and its transform

arrows(0, 0, v_regular[1], v_regular[2], col = "blue", lwd = 2)

arrows(0, 0, v_transformed[1], v_transformed[2], col = "blue", lwd = 2, lty = 2)

# Eigenvector and its transform

arrows(0, 0, v_eigen[1], v_eigen[2], col = "red", lwd = 2)

arrows(0, 0, v_eigen_transformed[1], v_eigen_transformed[2], col = "red", lwd = 2, lty = 2)

legend("topleft", c("Regular (original)", "Regular (transformed)",

"Eigenvector (original)", "Eigenvector (transformed)"),

col = c("blue", "blue", "red", "red"), lty = c(1, 2, 1, 2), lwd = 2)

# Symmetric matrix example

A <- matrix(c(4, 2, 2, 3), nrow = 2)

eig <- eigen(A)

# Eigenvalues

eig$values[1] 5.561553 1.438447# Eigenvectors (as columns)

eig$vectors [,1] [,2]

[1,] -0.7882054 0.6154122

[2,] -0.6154122 -0.7882054Verify the eigenvalue equation \(\mathbf{A}\mathbf{v} = \lambda\mathbf{v}\):

v1 <- eig$vectors[, 1]

lambda1 <- eig$values[1]

# These should be equal

A %*% v1 [,1]

[1,] -4.383646

[2,] -3.422648lambda1 * v1[1] -4.383646 -3.422648For symmetric matrices (like covariance matrices):

# Verify orthogonality: dot product = 0

sum(eig$vectors[, 1] * eig$vectors[, 2])[1] 0PCA performs eigenanalysis on the covariance (or correlation) matrix. Here’s the connection:

# Simple example with iris data

iris_centered <- scale(iris[, 1:4], center = TRUE, scale = FALSE)

cov_iris <- cov(iris_centered)

# Eigenanalysis

eig_iris <- eigen(cov_iris)

# Compare to PCA

pca_iris <- prcomp(iris[, 1:4], center = TRUE, scale. = FALSE)

# Eigenvalues = squared singular values = variances

eig_iris$values[1] 4.22824171 0.24267075 0.07820950 0.02383509pca_iris$sdev^2[1] 4.22824171 0.24267075 0.07820950 0.02383509The loadings from PCA match the eigenvectors (possibly with sign flips, which are arbitrary):

# Eigenvectors

round(eig_iris$vectors, 3) [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

[1,] 0.361 -0.657 -0.582 0.315

[2,] -0.085 -0.730 0.598 -0.320

[3,] 0.857 0.173 0.076 -0.480

[4,] 0.358 0.075 0.546 0.754# PCA loadings

round(pca_iris$rotation, 3) PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4

Sepal.Length 0.361 -0.657 0.582 0.315

Sepal.Width -0.085 -0.730 -0.598 -0.320

Petal.Length 0.857 0.173 -0.076 -0.480

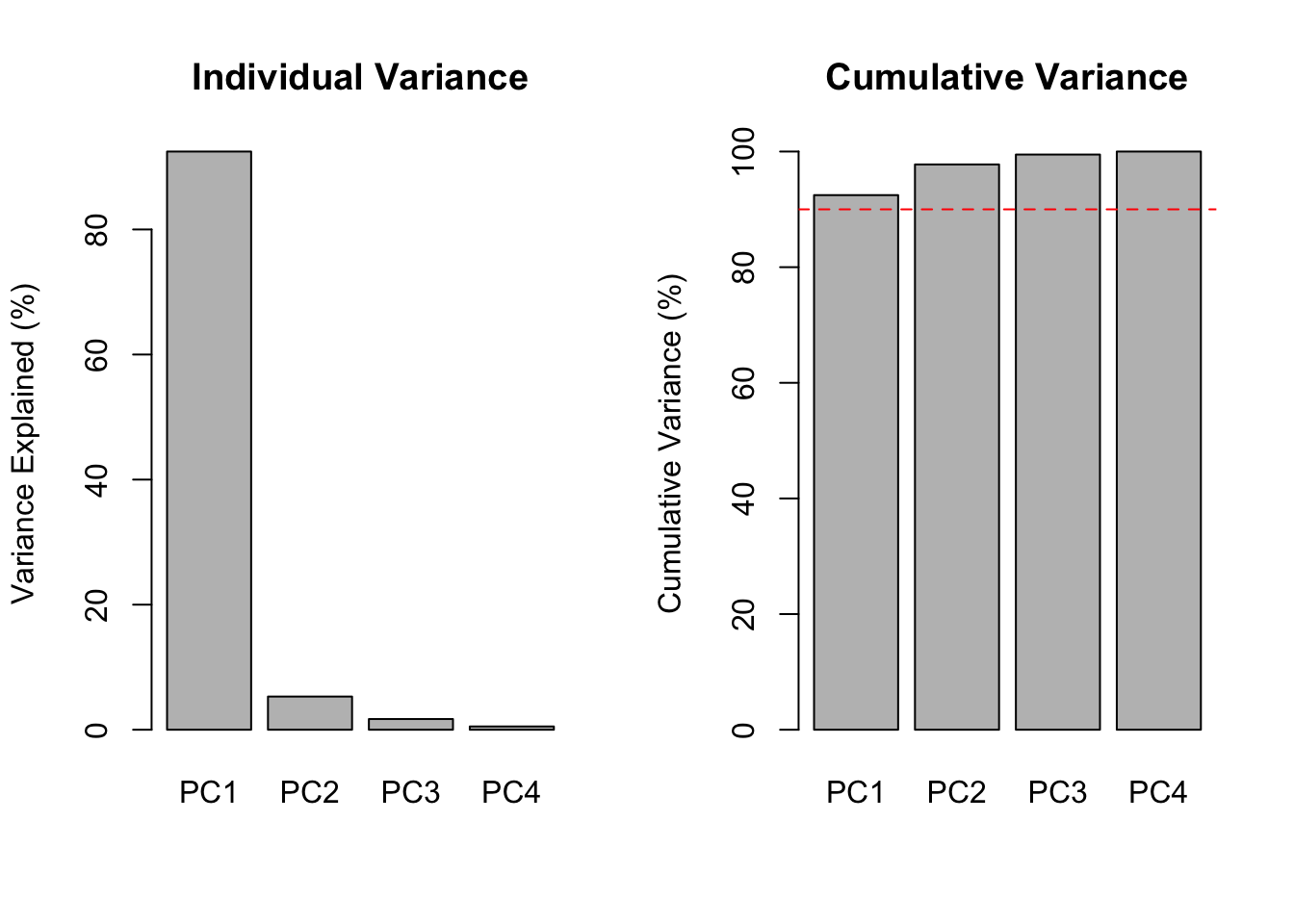

Petal.Width 0.358 0.075 -0.546 0.754Eigenvalues tell you how much variance each principal component captures.

# Compute proportion of variance

var_explained <- eig_iris$values / sum(eig_iris$values)

cumulative_var <- cumsum(var_explained)

par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

barplot(var_explained * 100, names.arg = paste0("PC", 1:4),

ylab = "Variance Explained (%)", main = "Individual Variance")

barplot(cumulative_var * 100, names.arg = paste0("PC", 1:4),

ylab = "Cumulative Variance (%)", main = "Cumulative Variance")

abline(h = 90, col = "red", lty = 2)

Key interpretations:

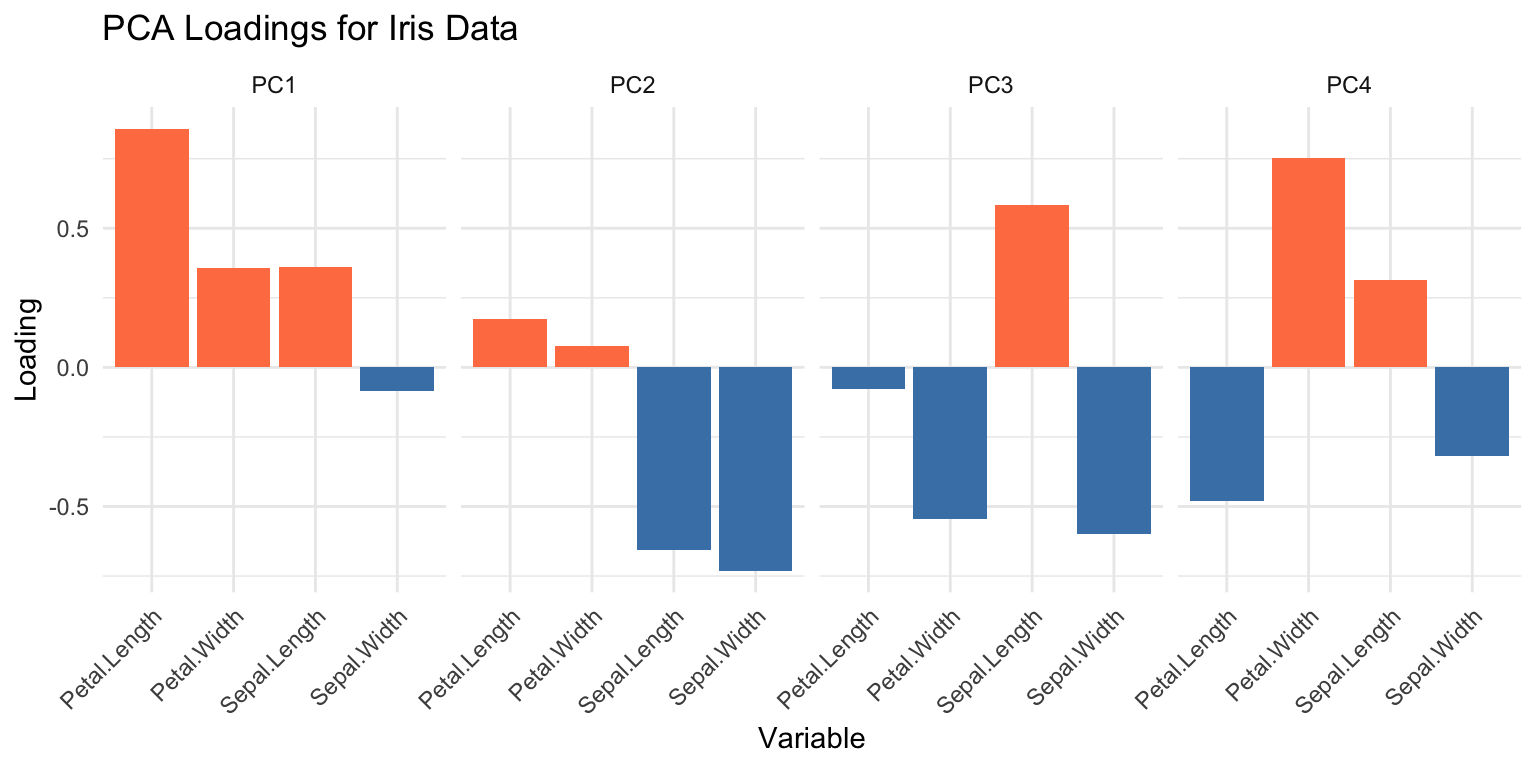

Eigenvectors tell you how original variables combine to form each PC.

loadings_df <- data.frame(

Variable = rep(colnames(iris)[1:4], 4),

PC = rep(paste0("PC", 1:4), each = 4),

Loading = as.vector(pca_iris$rotation)

)

ggplot(loadings_df, aes(x = Variable, y = Loading, fill = Loading > 0)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

facet_wrap(~PC, nrow = 1) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("steelblue", "coral"), guide = "none") +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1)) +

labs(title = "PCA Loadings for Iris Data")

Key interpretations:

A symmetric matrix can be decomposed as:

\[\mathbf{A} = \mathbf{V} \mathbf{\Lambda} \mathbf{V}^\top\]

where: - \(\mathbf{V}\) is the matrix of eigenvectors (columns) - \(\mathbf{\Lambda}\) is a diagonal matrix of eigenvalues

# Verify spectral decomposition

V <- eig_iris$vectors

Lambda <- diag(eig_iris$values)

reconstructed <- V %*% Lambda %*% t(V)

# Should match original covariance matrix

max(abs(cov_iris - reconstructed))[1] 8.881784e-16This decomposition is the mathematical basis for PCA’s ability to reduce dimensionality while preserving variance.

The inverse of a square matrix \(\mathbf{A}\), denoted \(\mathbf{A}^{-1}\), satisfies:

\[\mathbf{A}\mathbf{A}^{-1} = \mathbf{A}^{-1}\mathbf{A} = \mathbf{I}\]

where \(\mathbf{I}\) is the identity matrix.

A <- matrix(c(4, 2, 2, 3), nrow = 2)

A_inv <- solve(A)

# Verify

A %*% A_inv [,1] [,2]

[1,] 1 0

[2,] 0 1Matrix inversion is used in:

# Solve linear system Ax = b

A <- matrix(c(2, 1, 1, 3), nrow = 2)

b <- c(5, 7)

x <- solve(A, b) # More efficient than solve(A) %*% b

x[1] 1.6 1.8# Verify

A %*% x [,1]

[1,] 5

[2,] 7The QR decomposition factors a matrix as \(\mathbf{X} = \mathbf{QR}\) where:

This is numerically more stable than matrix inversion for solving linear systems.

qr_result <- qr(A)

Q <- qr.Q(qr_result)

R <- qr.R(qr_result)

# Verify

Q %*% R [,1] [,2]

[1,] 2 1

[2,] 1 3Key matrix algebra concepts for statistics:

| Operation | R Function | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Transpose | t(X) |

Swap rows and columns |

| Matrix multiply | X %*% Y |

Matrix multiplication |

| Cross product | crossprod(X) |

\(\mathbf{X}^\top\mathbf{X}\) |

| Element-wise ops | X * Y, X + Y |

Apply to each element |

| Row/column stats | rowMeans(), colSds() |

Summary statistics |

| Standardize | sweep(), scale() |

Center and scale |

| Eigenanalysis | eigen() |

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors |

| Inverse | solve() |

Matrix inverse |

| QR decomposition | qr() |

Orthogonal decomposition |

For PCA (see Chapter 37):

Create a 100 × 10 matrix of randomly generated normal numbers. Compute its dimensions, number of rows, and number of columns.

Add the scalar 1 to row 1, the scalar 2 to row 2, and so on, to the matrix from Exercise 1. Hint: create a vector 1:100 and add it.

Perform eigenanalysis on the iris covariance matrix. Which variable contributes most to PC1?

Verify that the eigenvectors are orthogonal by computing their pairwise dot products.

sweep().