42 Presenting Statistical Results

42.1 The Art of Scientific Communication

You have collected your data, performed your statistical analyses, and obtained results. Now comes a critical challenge that many students underestimate: communicating those results clearly and professionally. The results section of a scientific paper serves as the bridge between your methods and your conclusions, and writing it well requires understanding both statistical concepts and scientific writing conventions.

This chapter covers the practical aspects of presenting statistical results—the style conventions, formatting standards, and communication strategies that transform raw statistical output into compelling scientific narrative.

42.2 Style and Function of the Results Section

The results section has a specific purpose: to present your findings objectively and systematically, without interpretation or speculation. This section answers the question “What did you find?” while leaving “What does it mean?” for the discussion.

Writing Style Conventions

Scientific results are traditionally written in past tense and passive voice:

“The mean expression level was significantly higher in the treatment group compared to the control group (t = 3.45, df = 28, p = 0.002).”

Rather than:

“We find that the mean expression level is significantly higher…”

The past tense reflects that the research has been completed. The passive voice keeps the focus on the findings rather than the researchers. While some journals now accept active voice, the past tense remains standard for results sections.

Objectivity and Precision

Results sections should be factual and precise: - Report exact values, not vague descriptions - Avoid emotional or evaluative language - Let the numbers speak for themselves

Avoid: “The results were very impressive and showed a dramatic improvement.”

Better: “Cell viability increased from 45.2% (±3.1) to 78.6% (±4.2) following treatment.”

42.3 Summarizing Statistical Analyses

When reporting results, you need to convey what test you performed and what it revealed. The key elements include:

- The statistical test used

- The test statistic value

- Degrees of freedom (when applicable)

- The p-value or confidence interval

- Effect size (increasingly expected in modern publications)

Common Reporting Formats

Different statistical tests have standard reporting formats:

t-tests: > “Mean protein concentration was significantly higher in treated cells (M = 45.3 ng/mL, SD = 8.2) than in control cells (M = 31.7 ng/mL, SD = 7.4), t(48) = 6.12, p < 0.001, d = 1.74.”

ANOVA: > “Gene expression differed significantly among the three treatment groups, F(2, 87) = 15.34, p < 0.001, η² = 0.26.”

Chi-square test: > “There was a significant association between genotype and disease status, χ²(2) = 12.45, p = 0.002, V = 0.31.”

Correlation: > “Body mass was positively correlated with metabolic rate, r(58) = 0.67, p < 0.001.”

Regression: > “Temperature significantly predicted reaction rate, β = 0.82, t(43) = 7.89, p < 0.001, R² = 0.59.”

Formatting Statistical Symbols

Statistical symbols follow specific conventions:

- Use italics for statistical symbols: p, t, F, r, n, M, SD

- Do not italicize Greek letters: α, β, χ², η²

- Report exact p-values to 2-3 decimal places (p = 0.034) rather than inequalities (p < 0.05), except when p < 0.001

- Round most statistics to 2 decimal places

- Report means and standard deviations to one more decimal place than the original measurements

42.4 Reporting Differences and Directionality

Statistical tests tell you whether a difference exists, but your results section must also communicate the direction and magnitude of that difference.

Stating Directionality Clearly

Always specify which group was higher, lower, faster, or slower:

Unclear: “There was a significant difference between groups (p = 0.003).”

Clear: “The treatment group showed significantly higher expression levels than the control group (p = 0.003).”

Reporting Magnitude

Include the actual values so readers can judge biological significance:

Incomplete: “Treatment significantly increased survival (p < 0.01).”

Complete: “Treatment increased 30-day survival from 34% to 67% (p < 0.01).”

Effect Sizes

P-values tell you whether an effect is statistically distinguishable from zero; effect sizes tell you how large the effect is. Common effect size measures include:

| Statistic | Effect Size Measure | Small | Medium | Large |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-test | Cohen’s d | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| ANOVA | η² (eta squared) | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.14 |

| Correlation | r | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Chi-square | Cramér’s V | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

Report effect sizes alongside p-values:

“The drug treatment significantly improved memory scores, t(46) = 3.21, p = 0.002, d = 0.94, indicating a large effect.”

42.5 Units and Measurement

Always include units for measured quantities. Readers need units to interpret your findings.

Without units: “Mean concentration was 45.3 (SD = 8.2).”

With units: “Mean concentration was 45.3 ng/mL (SD = 8.2 ng/mL).”

SI Units

Use International System of Units (SI) consistently: - Mass: kg, g, mg, μg - Length: m, cm, mm, μm, nm - Time: s, min, h - Concentration: M, mM, μM, mol/L - Temperature: °C or K

Formatting Numbers

- Use consistent decimal places within a comparison

- Use scientific notation for very large or very small numbers: 3.2 × 10⁶ cells/mL

- Include leading zeros: 0.05, not .05

- Use spaces or commas for large numbers: 10,000 or 10 000

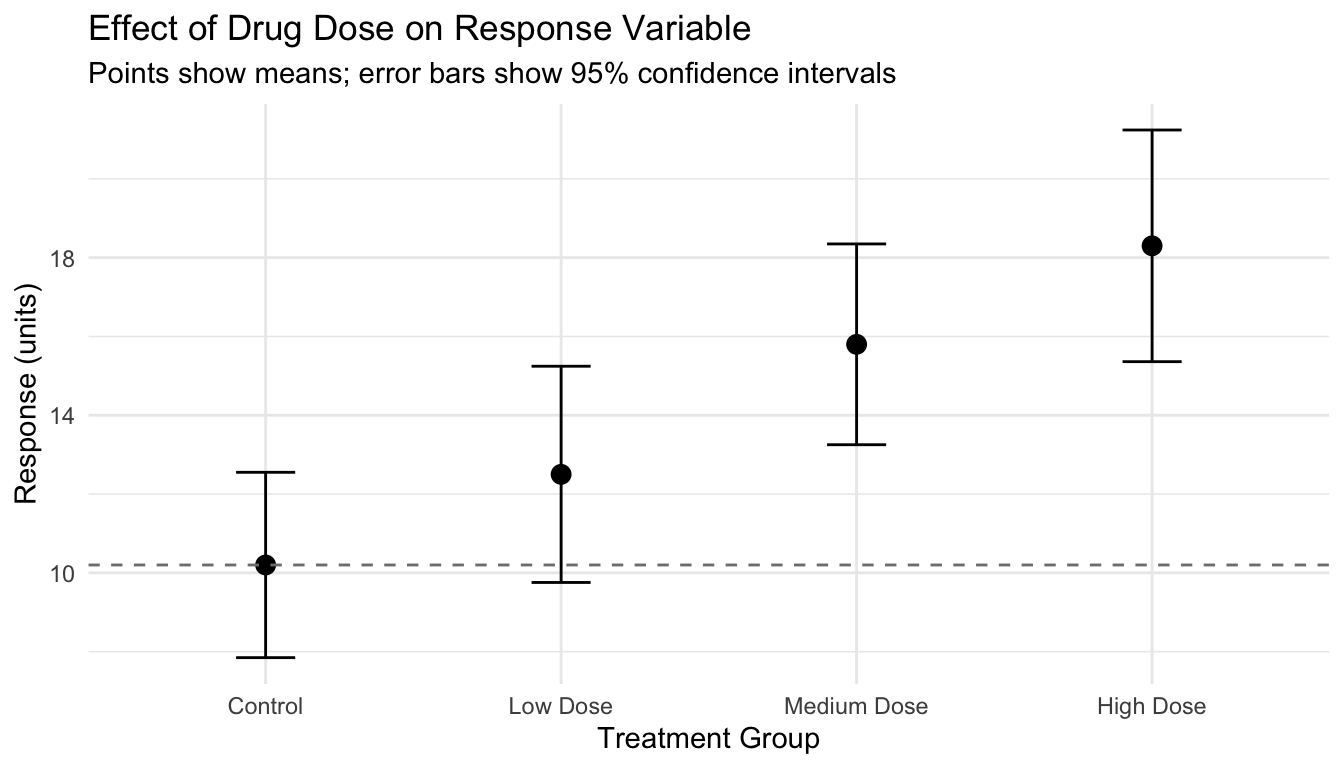

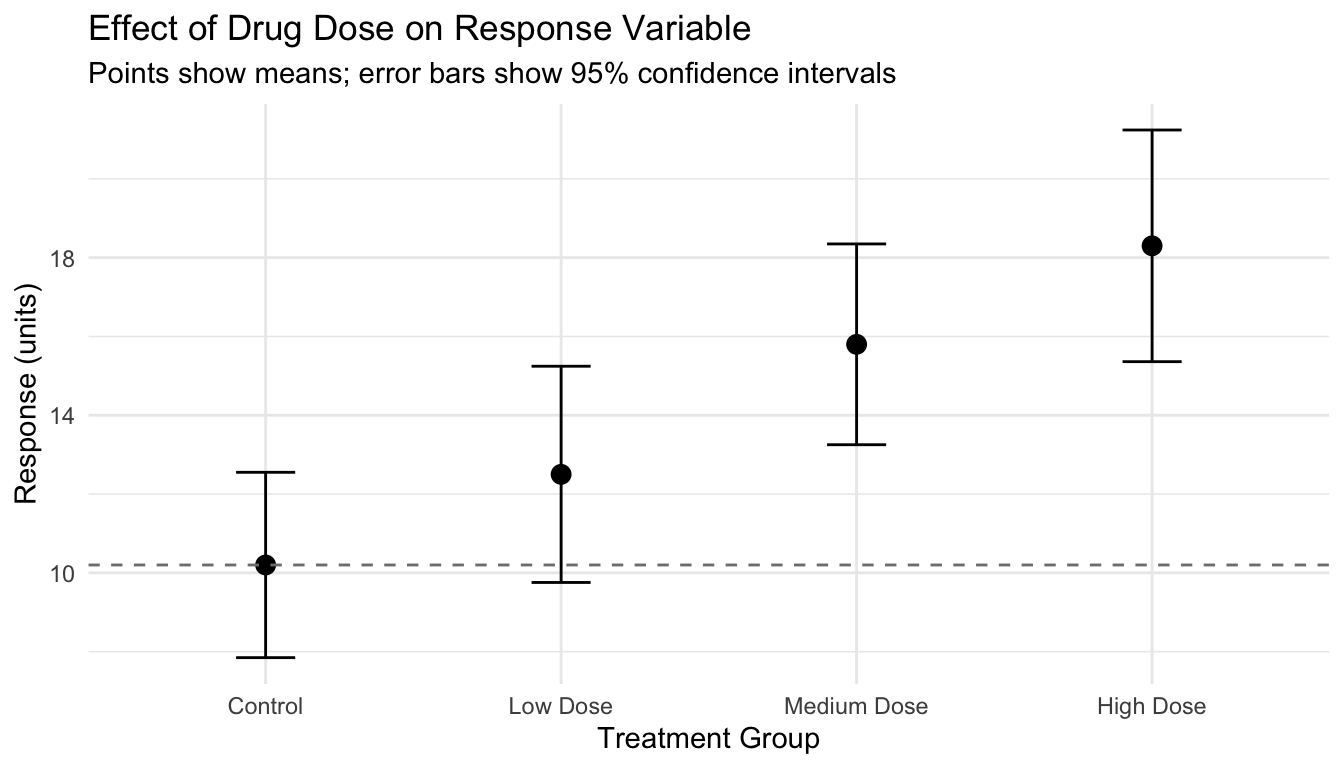

42.6 Integrating Text, Tables, and Figures

Effective results sections coordinate text, tables, and figures. Each serves a different purpose:

- Text: Highlights key findings and guides interpretation

- Tables: Present precise numerical values for comparison

- Figures: Show patterns, trends, and relationships visually

Referring to Figures and Tables

Every figure and table must be referenced in the text:

“Expression levels varied significantly among tissue types (Figure 3.2). The highest expression was observed in liver tissue, while muscle showed minimal expression (Table 3.1).”

Avoiding Redundancy

Don’t repeat the same information in text, table, and figure. Instead, present detailed data in tables or figures and summarize the key findings in text:

Redundant: “As shown in Table 1, Group A had a mean of 45.3, Group B had a mean of 52.1, and Group C had a mean of 48.7.”

Better: “Mean values differed significantly among groups (Table 1), with Group B showing the highest response.”

42.7 Non-Significant Results

Non-significant results are still results and should be reported clearly:

“There was no significant difference in survival rate between treatment and control groups (78% vs. 72%, χ²(1) = 1.24, p = 0.27).”

Report exact p-values for non-significant results rather than simply stating “p > 0.05” or “ns.” This gives readers information about how close the result was to significance and allows for meta-analysis.

A non-significant result means you failed to detect an effect—it does not prove no effect exists. Avoid language like “the treatment had no effect.” Instead use “we did not detect a significant effect” or “there was no significant difference.”

42.8 Handling Multiple Comparisons

When conducting multiple statistical tests, address the issue of multiple comparisons:

“To control for multiple comparisons, we applied Bonferroni correction, setting the significance threshold at α = 0.008 (0.05/6). After correction, three of the six comparisons remained significant.”

Or:

“We report uncorrected p-values but note that with 12 tests, approximately one significant result would be expected by chance at α = 0.05.”

42.9 Confidence Intervals

Confidence intervals often communicate more information than p-values alone. They show both statistical significance and precision of estimation:

“Mean improvement in the treatment group was 12.3 points (95% CI: 8.1–16.5), significantly greater than zero.”

When confidence intervals don’t cross zero (for differences) or one (for ratios), the result is statistically significant at the corresponding α level.

42.10 Practical Example: Writing a Results Paragraph

Consider an experiment testing whether a new fertilizer affects plant growth. Here’s how to construct a results paragraph:

Data summary: - Control group: n = 30, mean height = 24.3 cm, SD = 4.2 cm - Treatment group: n = 30, mean height = 31.7 cm, SD = 5.1 cm - t-test: t(58) = 6.17, p < 0.001 - Cohen’s d = 1.59

Well-written results paragraph:

“Plants receiving the experimental fertilizer grew significantly taller than control plants. Mean height in the treatment group (M = 31.7 cm, SD = 5.1) was 7.4 cm greater than in the control group (M = 24.3 cm, SD = 4.2), representing a 30% increase in growth. This difference was statistically significant, t(58) = 6.17, p < 0.001, with a large effect size (d = 1.59). Figure 1 shows the distribution of heights in both groups.”

Notice how this paragraph: - States the main finding clearly - Provides specific numerical values - Reports both percentage and absolute differences - Includes all statistical details - References a figure - Uses past tense and maintains objectivity

42.11 Common Mistakes to Avoid

Statistical Reporting Errors

- Misreporting degrees of freedom: For a t-test comparing two groups of 25 each, df = 48, not 50

- Inconsistent decimal places: Report “M = 45.32, SD = 8.10” not “M = 45.32, SD = 8.1”

- Missing test statistics: “p < 0.05” without the test statistic is incomplete

- Confusing SD and SE: Standard deviation describes variability; standard error describes precision of the mean

Interpretation Errors

- Claiming causation from correlation: Correlation does not imply causation

- Over-interpreting non-significance: Failure to reject H₀ is not acceptance of H₀

- Equating statistical and practical significance: A tiny effect can be statistically significant with large n

Presentation Errors

- Burying important results: Lead with key findings

- Mixing results and interpretation: Save interpretation for the discussion

- Incomplete reporting: Include all tests performed, including non-significant results

42.12 Reporting Guidelines and Standards

Many fields have developed reporting guidelines for specific types of studies:

- CONSORT: Randomized controlled trials

- STROBE: Observational studies

- PRISMA: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- ARRIVE: Animal research

These guidelines specify what information to report and how to structure your presentation. Following them improves transparency and reproducibility.

42.13 Creating Reproducible Results

Modern scientific practice increasingly emphasizes reproducibility. Consider:

- Report exact values from statistical software rather than rounded approximations

- Include sample sizes for all analyses

- Describe any data exclusions and the rationale

- Note software and versions used for analysis

- Share data and code when possible

Code

# Example: Extracting exact values for reporting

# Instead of rounding manually, extract from model objects

model_data <- data.frame(

treatment = rep(c("Control", "Drug"), each = 20),

response = c(rnorm(20, 50, 10), rnorm(20, 58, 12))

)

t_result <- t.test(response ~ treatment, data = model_data)

# Extract values programmatically

cat("t =", round(t_result$statistic, 2), "\n")t = -0.68 Code

cat("df =", round(t_result$parameter, 1), "\n")df = 38 Code

cat("p =", round(t_result$p.value, 4), "\n")p = 0.5028 Code

cat("95% CI: [", round(t_result$conf.int[1], 2), ",",

round(t_result$conf.int[2], 2), "]\n")95% CI: [ -11.29 , 5.64 ]42.14 Summary

Presenting statistical results effectively requires:

- Proper style: Past tense, passive voice, objective tone

- Complete reporting: Test statistic, degrees of freedom, p-value, effect size

- Clear directionality: State which group was higher/lower/faster

- Appropriate precision: Consistent decimal places and units

- Integration: Coordinate text, tables, and figures without redundancy

- Transparency: Report all results, including non-significant findings

The goal is to present your findings so clearly that readers can evaluate the evidence themselves. Statistical results should inform, not obscure. Master these conventions, and your scientific writing will communicate with precision and authority.

42.15 Additional Resources

- American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.) - The standard reference for statistical reporting format

- Lang, T. A., & Secic, M. (2006). How to Report Statistics in Medicine - Medical statistics reporting guidelines

- Thulin (2025) - Modern approaches to presenting statistical analyses