43 The Eugenics History of Statistics

43.1 Why This History Matters

Many of the statistical methods we use today—correlation, regression, ANOVA, and others—were developed by scientists whose primary motivation was eugenics. Understanding this history is important not to discredit the methods themselves, which remain mathematically valid and useful, but to understand the context in which science develops and to remain vigilant about how scientific tools can be misused.

Science does not exist in a vacuum. The questions scientists ask, the data they collect, and the interpretations they favor are shaped by the social contexts in which they work. The history of statistics and eugenics offers a stark example of this principle.

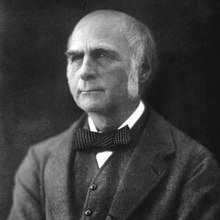

43.2 Francis Galton: Founder of Eugenics

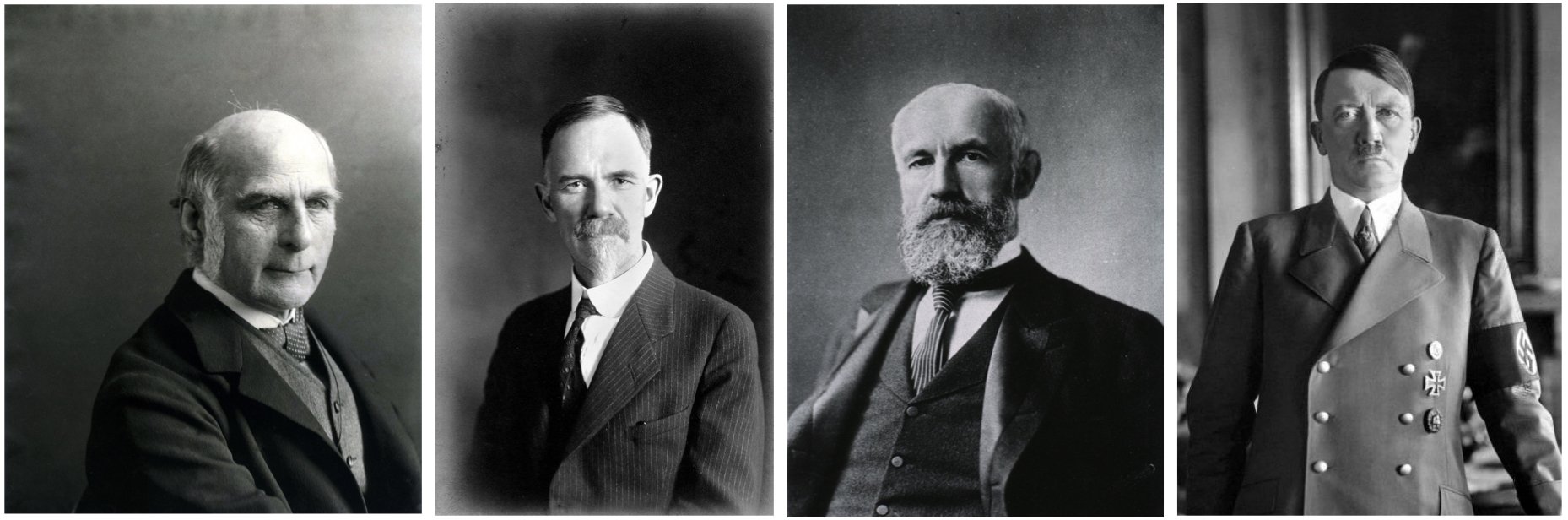

Francis Galton (1822–1911) was Charles Darwin’s half-cousin and a polymath who made genuine contributions to statistics, meteorology, and other fields. He invented correlation, pioneered the use of questionnaires, and conducted early twin studies. He is also the person who coined the term “eugenics” and devoted much of his career to promoting it.

Galton believed that human intelligence was hereditary and that the “improvement” of the human race could be achieved through selective breeding. He studied prominent academics and concluded that talent ran in families, attributing this entirely to heredity while ignoring the advantages of wealth, education, and social connections.

His statistical innovations—correlation, regression to the mean—were developed specifically to analyze human inheritance and support eugenic arguments. The concept of “regression to the mean” came from his observation that tall parents had children who were tall but not as extremely tall as the parents, which he interpreted through a lens of hereditary “quality.”

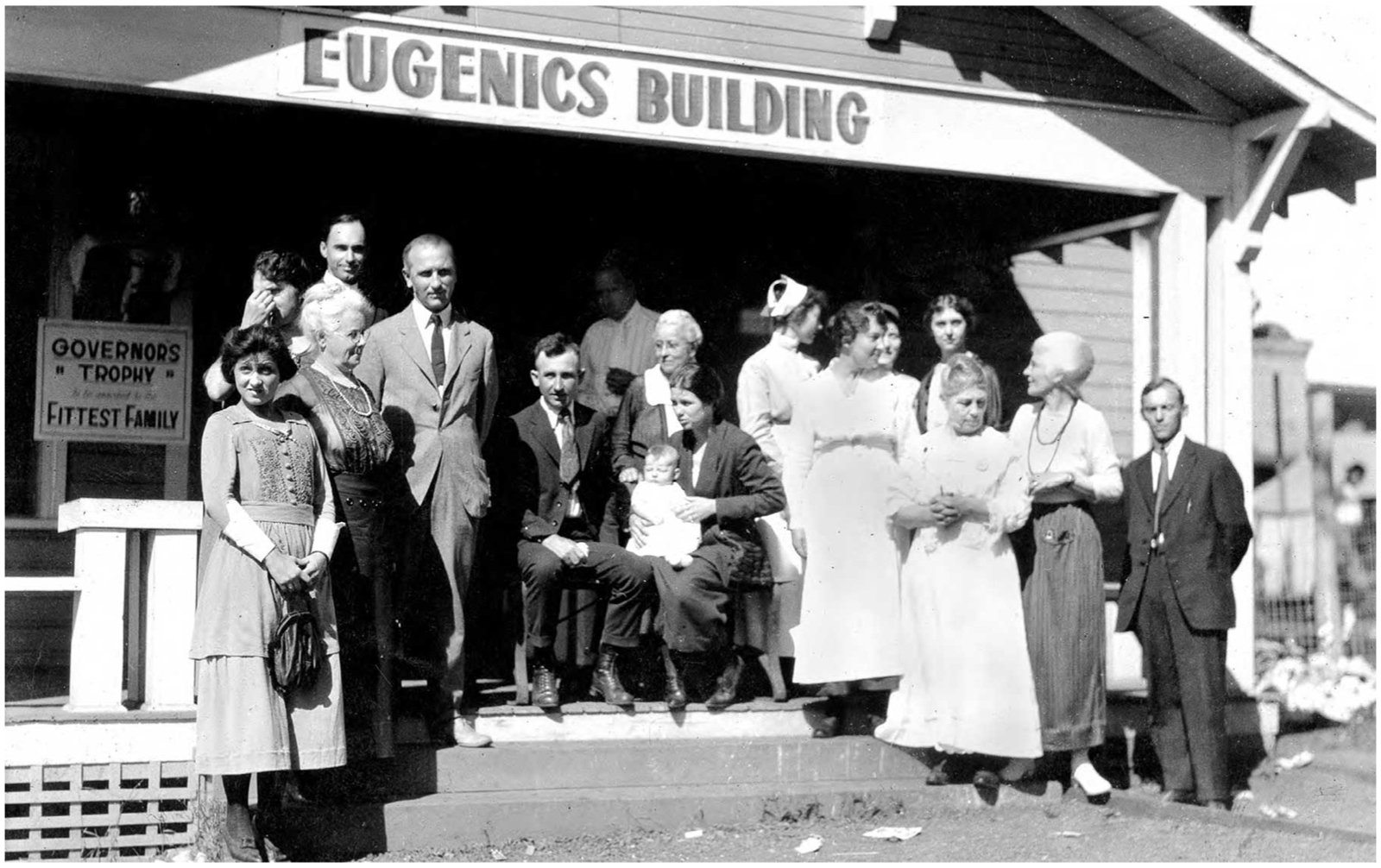

43.3 Eugenics in America

Eugenic ideas found fertile ground in the United States. The Eugenics Record Office (ERO) was founded at Cold Spring Harbor in 1910, conducting research aimed at identifying “unfit” individuals who should be prevented from reproducing.

State fairs featured “fitter family” contests. Educational materials promoted eugenic thinking. Thirty states passed laws allowing forced sterilization of people deemed “unfit”—a category that disproportionately targeted poor people, immigrants, people with disabilities, and people of color.

Between 1907 and 1963, over 64,000 people were forcibly sterilized in the United States under eugenic legislation. California led the nation in forced sterilizations.

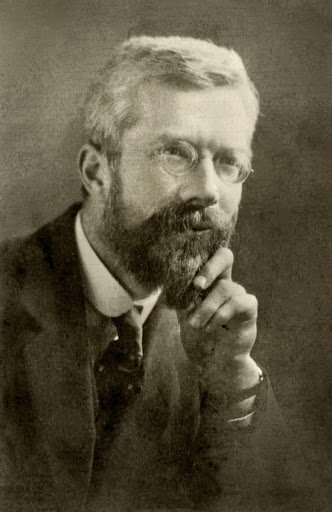

43.4 R.A. Fisher and Eugenics

Ronald A. Fisher (1890–1962) is one of the most influential statisticians in history. He developed analysis of variance (ANOVA), the concept of statistical significance, maximum likelihood estimation, and experimental design principles that remain standard today.

Fisher was also deeply committed to eugenics throughout his career. He was the founding chairman of the Cambridge University Eugenics Society. Approximately one-third of his landmark book “The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection” (1930) addresses eugenics, arguing that the fall of civilizations was caused by differential fertility between social classes.

Fisher used his statistical methods to analyze human variation in ways meant to support racial hierarchies. His scientific work and his eugenic advocacy were not separate activities—they were intertwined.

43.5 Connections to Nazi Germany

American eugenics directly influenced Nazi Germany. The Nazi sterilization program, which forcibly sterilized hundreds of thousands of people, was explicitly modeled on American laws, particularly California’s.

The Holocaust itself was the most extreme expression of eugenic ideology—the belief that human populations could and should be “improved” through preventing certain people from reproducing, taken to its murderous conclusion.

After World War II, the horrors of Nazi eugenics discredited the movement publicly, but eugenic practices continued. Forced sterilizations continued in the United States into the 1970s. California did not pass legislation explicitly banning sterilization of prison inmates until 2014.

43.6 What Do We Do With This History?

The statistical methods developed by Galton, Fisher, and others are mathematically sound. A t-test does not care about the motives of the person who developed it. These tools have been used to improve medicine, agriculture, and countless other fields.

But acknowledging this history serves several purposes:

It reminds us that science is not neutral. The questions scientists ask are shaped by their values and social context. Eugenic statistics were developed to answer eugenic questions.

It encourages vigilance. Similar misuses of science can occur today. Claims about genetic differences between groups, about who deserves resources or rights, should be scrutinized carefully.

It honors the victims. Tens of thousands of people were forcibly sterilized, and millions were murdered, under policies justified by scientific authority. Acknowledging this history recognizes their suffering.

43.7 Moving Forward

Understanding this history does not mean abandoning statistics—it means using these tools thoughtfully and ethically. It means being skeptical when scientific claims align too conveniently with existing prejudices. It means recognizing that data and analysis can be weaponized.

Science has the potential to improve human welfare, but only when practiced with awareness of its history and constant attention to its ethics.

43.8 Further Reading

For those interested in exploring this history further:

- “Superior: The Return of Race Science” by Angela Saini

- “The Gene: An Intimate History” by Siddhartha Mukherjee

- “Control: The Dark History and Troubling Present of Eugenics” by Adam Rutherford